What An Evening At Purdah Bagh In Old Delhi Says About Women And Leisure

Are segregated parks for women the solution to a city’s heavily male-dominated leisure spaces? Even as urban planners and feminists argue, we take a walk in Old Delhi’s historical zenana parks to find some answers

“Jahan chaar ladies ek sath hoti hain, toh samajh jao ki woh kya baatein karti hain (when four women come together, you know where the conversation will head),” says Sushila, as she and a group of seven women in their 60s and 70s burst into guffaws. “Aadmiyon ki buraiyan (criticise men),” someone responds, and the group is in splits once again.

Tucked into the walled city of Old Delhi, in the midst of the busy bylanes of Daryaganj, is a rare space – a park that is only for women, the Purdah Bagh. This is where we find a bunch of best friends who have been visiting this park for the last three decades, never missing a day.

“Buri aadat hai yeh hamari ab toh. Aaye bina reh nahi sakte (it has become a bad habit, one we can’t resist). We enjoy this space because men cannot come here, and because we can talk about everything. We sometimes phone in the kulfiwala and have a field day,” says Geeta Mehra, a resident of Daryaganj in her late 70s.

For most women like Mehra, leisure is a ‘buri aadat’, a guilty pleasure. Data show why: an average Indian woman spends 243 minutes on unpaid domestic work or caregiving, and a man 25 minutes. Leisure is a rare privilege for many women, as Surbhi Yadav has documented.

Here, behind the tall walls and hedges that veil them from the masculine spaces outside, you will find women and young girls unwinding, their burqas flung aside, pallus and dupattas carelessly draped. You may also spot a young woman walking in search of privacy and make a phone call.

Gender segregated enclaves are the subject of multiple debates. Shilpa Phadke, Sameera Khan and Shilpa Ranade in their book, Why Loiter, argue that while such spaces reinforce gender differences, the many women they interviewed said that their families would not allow them to relax anywhere else.

Creating limited spaces for women or dictating a curfew to ensure their “safety” does not resolve the issue of gender violence in public places either, it has been argued. Without a systemic approach, segregation will only partially address the issues of women’s access, mobility and agency, as this Behanbox article had argued.

However, women-only parks are becoming an increasingly popular idea with urban authorities: Hyderabad, Bhopal and Mumbai also have exclusive parks for women. Delhi ambitiously plans to build 250 odd women-only parks, or ‘Pink Parks’. One has already been piloted in Mata Sundari Road, near the Ramlila Maidan.

‘A Place To Loiter’

The Purdah Bagh is one of old Delhi’s three historic zenana/mahila (women-only) parks built in the mid-17th century. Apart from the one at Darya Ganj, there is another in Chandni Chowk, and one more near Jama Masjid. Men’s entry is strictly restricted and only children up to five years of age are allowed in.

When we walk into the Purdah Bagh at Chandni Chowk, three women and children are having a picnic at the park that is monsoon-lush with trees and grass and calm despite the noise outside. There are bottles of cold drinks, crisps scattered around.

Rehana (36), Aiman (28) and Heena (40)* live in Daryaganj’s cramped lanes. Rehana and Aiman are daughters-in-law of the same family, while Heena is their sister-in-law who lives in Chandni Chowk. The two of them often make plans to meet Heena outside the house. “We come here with our children because they love playing here. It also gives us some time off from sitting in our houses where there isn’t enough space for everyone. The weather now is so hot so we take off our burqas and sit here,” says Rehana.

There is a sense of abandon in the women’s enjoyment of the place. Their children spiritedly run from one slide to another and every once in a while the women burst into uproarious laughter. After this, the three of them plan to go to Jama Masjid. “We will just roam around and maybe get something to eat,” says Aiman.

Heritage structures in India show up several gender-partitioned public spaces. Zenanas and other kinds of enclosures were a common feature in the palaces of Rajput kings and Mughal emperors. The Jhanki Mahal in the 15th century Mehrangarh fort in Jodhpur is one example. The jharokhas (latticed windows) of the women’s quarters at the Hawa Mahal in Jaipur are another example as are the royal harems of the Mughals. In her book, Royal Mughal Ladies And Their Contributions, historian Soma Mukherjee writes of the Meena Bazar in Old Delhi, which used to be a market run by women and for women sometime between the 16th and 19th century.

Jahanara’s Pleasure Park

In South Asian societies, ‘purdah’ has several connotations. While it literally means a curtain or a veil, it also refers to the physical segregation of genders and the cultural and religious practice of women covering their face or/and body.

In the 17th century, Mughal princess Jahanara Begum, built several walled women-only gardens in Old Delhi. Amita Sinha and Ayla Khan in their book Gender And The Indian City document how Jahanara and her sister Roshanara led the building of many gardens, market squares and serais (rest houses) in Shahjahanabad (now Old Delhi), their father Shah Jahan’s newly built capital.

One such garden was the “Begum ka Bagh” built by Jahanara in 1650 CE for the exclusive use of royal women. Legend has it that a curious Persian poet in the court had disguised himself in a burqa and entered the park but gave himself away when he recited a poem on Jahanara’s charms. She is believed to have graciously handed him a purse filled with coins, and then asked him to make a run for it. City historians say the three zenana parks were likely a part of this expansive bagh.

‘We Exercise, Sometimes Break Into A Dance’

In Daryaganj’s Hindi Park, there is a women-only section, marked by only a tall hedge that doubles up as ‘purdah’. But no one is complaining. “We exercise, do yoga here. Saree hamari oonchi bhi ho jaye, toh parwah nahi. Koi nahi hain dekhne ko. Sometimes in the middle of our exercise, we break into a dance,” says Bimla (72).

Most of the older women who come here are neighbours or live in neighbouring areas. “This is also a space where we discuss our health issues and give tips to each other. We share our joys too and sorrows and when we talk then the pain doesn’t seem that insurmountable,” says Bala Tomar (65).

The park, the women say, gives them a space to come together to talk about things ranging from Prime Minister Modi’s political style to the Asia Cup. “Hanging out here regenerates us. We sometimes sit here and plan outings, to cinema, tambola games and golgappa sessions. We had recently gone to see the G20 decorations at the Shaheedi Park,” says Sushila (70).

Fiza Haider is a researcher and women’s rights activist who has studied the use of public spaces by Muslim women. She recalls that the first time she went to the Purdah Bagh in Jama Masjid, she felt suffocated by its tall walls. “Jahanara’s intention behind these baghs were to strike a balance between women’s right to go out while being still ensconced within the tradition of purdah,” she says. “But after entering and seeing women inside, I felt much more at ease. It felt like a space where women can feel freer and build sisterhoods.”

She recalls being told by Muslim women in Delhi and Lucknow, her home city, that they sensed “hyper surveillance” when they entered a public space and they would wear the burqa to deal with this. “But I have also heard women say that unlike other parts of Delhi they feel free to go out at any hour in Old Delhi because yeh toh apna heen ilaka hain (this is our turf),” says Haider.

Space For Solidarity, Celebration

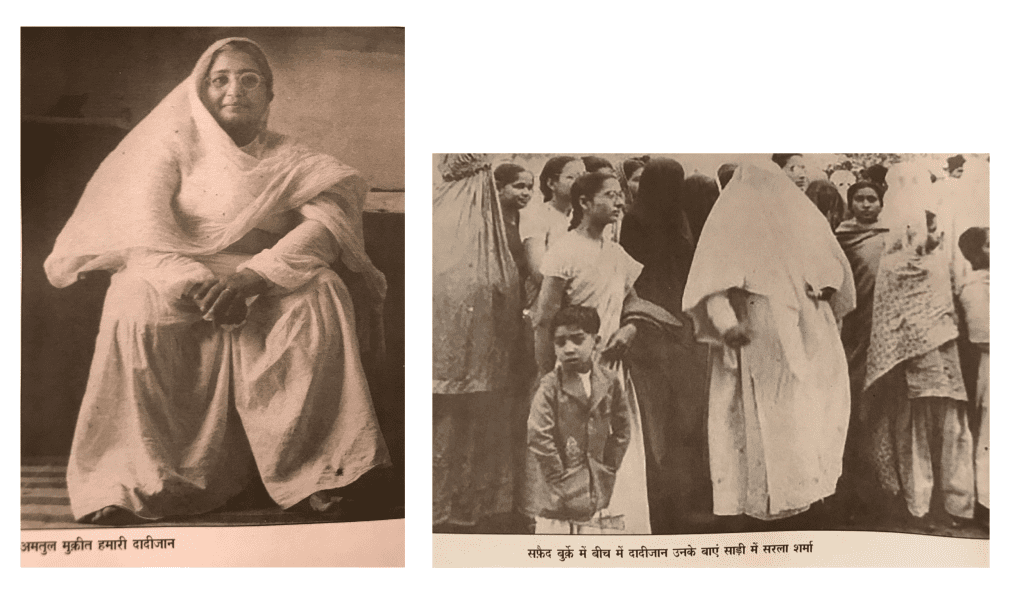

Writer and filmmaker Sohail Hashmi says that during the pre-Independence struggle his grandmother, Begum Hashmi, would hold political meetings inside the Jama Masjid park. A lot of women’s organisations, such as the Mahila Congress would also assemble there, he adds. Begum Hashmi went on to be the founding president of the Delhi committee of National Federation of Indian Women, the women’s wing of the Communist Party of India (CPI).

“One time, my grandfather, also part of the CPI, came home and found the house locked. He realised that my grandmother must be addressing a meeting in the park. He went to the park but wasn’t allowed inside. So he told the two Pathan woman guards on duty to inform his wife that he needed the key,” Hashmi recounts.

The park was also the location of neighbourhood celebrations of Basant Panchami, Sawan ka Tyohaar, and the Teej Mela, when women across communities congregated, says Hashmi.

While growing up, Rehana also remembers the Teej Mela being celebrated in the Purdah Bagh of Jama Masjid. “In the 70s, things looked different in the park. It used to be a more vibrant space – chaatwalas and chooriwalas would set up their stalls inside, and we would celebrate different festivals, like Teej. None of that happens any longer.

Even today, public parks are a safe space to collectivise. For instance, domestic workers unions meet in parks to avoid eviction from their homes. Delhi University’s women students have used the Central Secretariat lawns to strategise their protest against hostel curfews. And domestic workers in Neb Sarai’s Freedom Fighter Enclave meet every month at the neighbourhood Chhatriwali Park to pool in money and help each other out.

‘Bring Women Into Urban Planning’

Despite stated plans to revive the Chandni Chowk park, parts of it are overgrown and neglected and the lighting is not reliable at all times. And the women say this makes them anxious. Puran Singh, the park’s caretaker, says the footfall has fallen considerably over the past decade. There was earlier a silai (tailoring) centre in the area and its trainees would drop in at the park but once that shut down, the lawns saw fewer visitors.

Aiman, Rehana and Fatima too don’t come to the park regularly, but sometimes when they are in the area. “It doesn’t have a lot of facilities. We wish there was provision for bathrooms and drinking water here. That would help a lot,” says Rehana.

Researchers Sinha and Khan also interviewed several women visitors to these parks in 2009-10. Most complained that the streets outside were crowded and the men stared at them till they entered the park. They also reported that the men living in the tall buildings around the parks would watch them. Because the parks are large and have no lighting, women said they felt unsafe after dusk. Even during the day if there were no other women around, they would feel uncomfortable, they said.

Among planners and architects, there is a lack of vision when it comes to gender-inclusive spaces, says Saleha Sapra, co-founder of the urban collective City Sabha. This is why when women prepare the maps of a city, it looks a lot different. “That’s what we found when we did a map-making practice with women street vendors of Raghubir Nagar. Their maps accounted for things that planners don’t look at – neglected streets, neglected parks, well-maintained streets – information that is crucial for women’s mobility in public spaces,” says Sapra.

Aiman, Rehana and Fatima say they are happier going to the newly revamped Chandni Chowk for a late-night stroll. “Here the park closes at 7pm, so we can’t come here. But in Chandni Chowk, there is so much vibrancy, so many stalls, and many people around. We feel safer,” says Rehana.

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.