Indian Women Have No Say In Their Own Healthcare. Here Is How That Can Be Changed

Guwahati: One evening, my partner and I were comparing notes after work. “I had to explain the prognosis of a female patient to her next-door neighbour,” he said. Sensing a story I asked him: “Did she have no family?” “She does,” he replied. “But all her next of kin are women.”

While this may surprise some, it is a routine practice in hospitals and clinics around India. “Where is the man of the house?” is the standard question most physicians ask before breaking any news to the patient or their family. Doctors also prefer to update male bystanders about the patient’s condition and discuss treatment options with them. Many healthcare professionals understand that most of the cash flow in many Indian families is controlled by the men and hence, most household decisions, health-related or otherwise, are often made by them.

Health Decisions, An Indicator Of Autonomy

“Indian women do not even make their own healthcare decisions,” says Mohammad Aslam Ali, my partner and a senior resident of dermatology in Guwahati. “Doctors eventually start adopting this approach also because after spending a lot of time explaining to the woman, she almost always says, ‘Could you explain this to my father/husband/brother?’ So they stop explaining to women because they may have to explain twice.”

Making health-related decisions for oneself is one of the many indicators of autonomy. The others are freedom of movement, access to income, participation in the labour force and the ability to make financial decisions. Many indices calculating female autonomy include the ability to make health decisions for oneself as one of the prominent markers. However, it is a right still denied to most Indian women due to cultural reasons.

‘It Is A Family Decision’

“Whenever I explain their reproductive choices or breastfeeding options to women, they always say the decision is not theirs to make.It is a family decision,” says Shaba Fathima, who works in a rural community health centre in Chittoor, Andhra Pradesh. “Sometimes families decide to go against my advice and follow traditional wisdom instead. I can only indicate to them that it will be harmful to the woman’s health. I can see that most of the women who come to me do not have an inch of autonomy over their bodies. It makes me very sad.”

Though in India a woman does not need a husband’s consent to have an abortion, this right appears to be only on paper, as Behanbox has reported (here, here and here). Many healthcare providers feel uncomfortable offering reproductive care such as contraception and abortion to unmarried women or women unaccompanied by their husbands and hence they request spousal consent.

Sometimes, relatives even request doctors to hide from a woman the diagnosis or details of her illness. Also known as “collusion”, this mostly happens in the setting of a terminal illness. Relatives do the same because they feel the woman will be unable to handle the news or that she may want to give up instead of getting the disease treated. Studies done on collusion in India reveal that while this may happen with both genders, it is statistically much more likely to occur if the patient is a woman. Thus important health information about the self is also likely to be hidden from women.

I also remember a patient who had an unknown primary adenocarcinoma with bone marrow metastasis admitted to the medical oncology department of CMC Vellore. When we explained her condition at her request, she burst into tears and thanked us. She said that nobody from the healthcare team had spoken to her throughout her admission. They had only spoken to her relatives who kept the information from her and this only served to increase her fears and feeling of hopelessness.

Not Enough Information

A study published in the Indian journal of obstetrics and gynecology in 2015 audited the informed consent procedure before a Caesarean section by asking the women what they were explained before they signed the consent form. This study reveals that only 25% of the women received information about the steps of the medical procedure and its likely complications before signing.

A similar study published in the journal of biosocial science in 2020 on contraceptive choice reveals that only 36% of women using a modern contraception method had received the required information about the other options available to them. These facts also raise troubling questions about whether informed consent given by female patients is valid because healthcare providers do not seem to have given them enough information to make empowered decisions.

Many studies show good health outcomes associated with women having the autonomy to make healthcare decisions. The UN’s sustainable development goals for women also identify its absence as one of the key barriers to establishing universal access to women’s health. And while the barriers towards helping women establish this autonomy are socio-cultural – such as living in joint families, limiting religious beliefs, lack of education and lack of employment – it is also worth noting that India’s healthcare system has not done much to help women become more active participants in their own health decisions.

Gender Autonomy In Medical Training

Sadly, there is a lack of education and training programmes to help young physicians learn how to navigate these problems. Though preventive and social medicine is a part of medical training, it fails to address the multifaceted problem of lack of female autonomy and also does not teach physicians how to navigate the complexities of gender in their practice.

To foster female autonomy in medical practices, a commitment from healthcare professionals is needed to ensure that a woman gets to hear all of the health information necessary for her in a calm, non-threatening and non-judgemental environment is of paramount importance. All information must be provided to every woman regardless of who makes the final healthcare decision, even if that means explaining the same thing twice or thrice.

Shaba Fathima also says that she is constantly vigilant when she is counselling women about topics such as teen pregnancy and contraception because she would not want to shame their lack of knowledge or agency. “I had to read a lot of feminist discourse to learn the right language to employ in such situations,” she says. It was an eye-opening moment for me when she pointed out that many doctors shame underprivileged women for being oppressed. I remember all the times I have heard female patients indirectly point to their lack of agency with words such as “What can a woman do without a man?” Mostly female doctors tend to bristle at these words and launch into lectures about women’s empowerment. Having been guilty of this myself, I can now see the call for help for what it is.

Asking a woman what she wants for herself, independent of what the family wants, and helping her convey her wishes to them is also one way healthcare professionals can help women get heard.

Sensitising Medical Professionals

“A patient I used to see a woman who had three children under the age of 3.5,” says Noopur Kulkarni, a paediatrician who attends deliveries for the purpose of neonatal resuscitation. “When I asked her about contraception, she said her husband did not allow her to use contraception but also refused to stop having sex with her. My medical education did not prepare me for the ground reality of women not having any autonomy over what happens to their bodies. I wish I was taught how to handle these situations.”

“The problem is so widespread that this should be a part of our curriculum”, says Priya Sharma, practicing in Pune, “Though patient autonomy was taught to us as a general concept, we were never taught about the Indian context where there are issues which ensure that women do not get to have a say. Sometimes, even the women don’t know they could have a say.”

Including a systematic study of gender in the Indian context and its impact on healthcare in the medical education system will sensitise Indian doctors to be more mindful in their everyday practice. Campaigns and education aimed at eliminating the moralistic view of sex and reproductive health among doctors are also important. Informed consent aids with images or videos will also help any woman undergoing a medical procedure understand it better and give empowered consent. This integration of gender study into the curriculum will help Indian doctors advocate for their patients effectively.

“Any training programme that teaches us how to counsel women about their own legal rights and autonomy over their bodies and that can teach us on how to encourage them to take their own final decisions in the absence of relatives or a husband would go a long way,” says Priya. “I would definitely want something like that in my curriculum.”

Systems And Solutions

“Leaving no one behind” is the 2030 agenda for Sustainable Development. To this end, many interventions have been introduced and studied in India to identify strategies that can help increase female autonomy, including in the field of health.

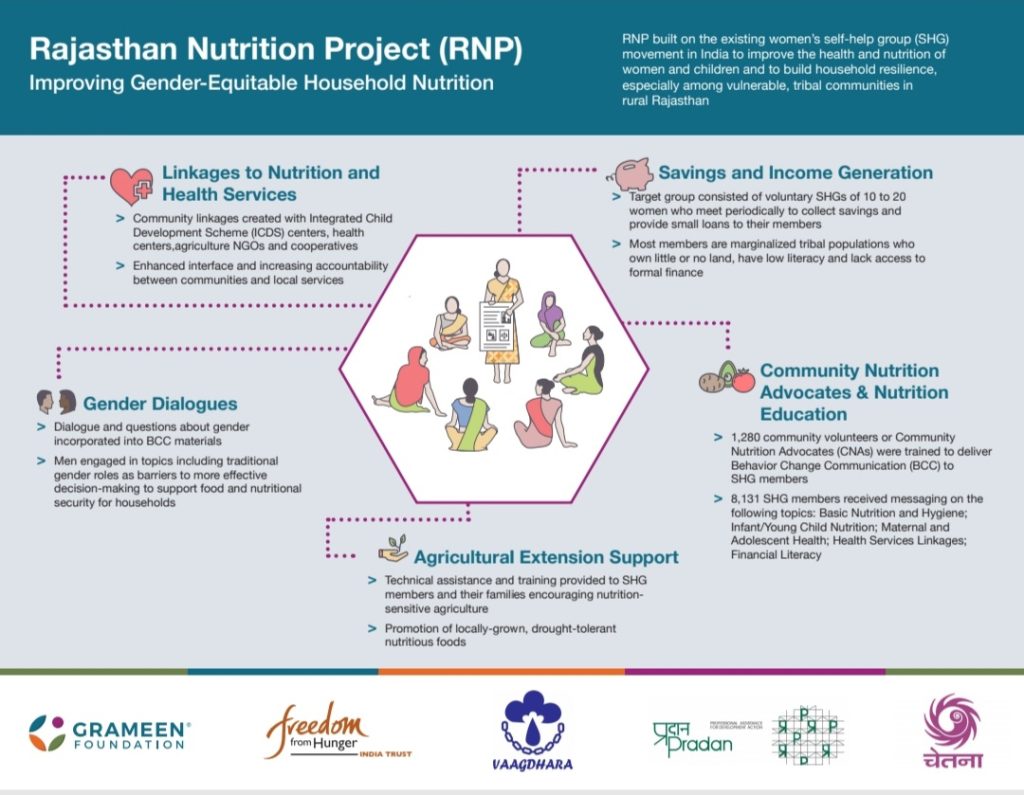

One such intervention is the Rajasthan Nutrition Project (RNP) introduced in 2015. Though initially introduced as a measure to reduce food insecurity in women and children in Rajasthan, the project also included educational components such as classes on financial management and planning for good nutrition for the family. Dialogues on gender and equity were also fostered as a part of the programme which was built for women’s self-help groups.

When the programme was launched, Rajasthan’s indices for women’s empowerment were some of the lowest in the country – only 25% of women being able to make decisions on their households and only 35% were a part of the state’s workforce. (Compare this with 99% in Nagaland for decision-making and 47% in Himachal for workforce participation.) Rajasthan was also one of the most food insecure states in the country with 39% of under five children being stunted.

The programme wanted to decrease food insecurity by increasing the ability of women to make good decisions for their households. Upskilling of women in both avenues of income generation as well as savings was done as well. A survey done in 2019 showed that in the four years after the implementation of the project, the indicators of autonomy, as well as food security, had increased substantially in Rajasthan.

Here are the domains where the improvements were noted.

Alongside the improvement in female autonomy, the nutritional indices have also improved in Rajasthan over the last four years as demonstrated by the Rajasthan state fact sheet (2019 to 2021)

Similarly a poverty alleviation scheme called the Pudhu Vaazhvu Project in Tamil Nadu was launched with the dual goal of poverty alleviation alongside improving female autonomy and has functioned with some success. Launched in 2005, the intervention focussed on microfinance, by giving small loans to women and upskilling them to encourage them to participate in the labour force. A survey done in 2015, 10 years after the launch of the project, revealed that more women have a say (around 10% more) in the intra-household decision making as compared to areas where this intervention is not implemented.

While these interventions may have increased measures of female autonomy indirectly and may have impacted health decision making, there are no specific interventions focussed on the latter goal.

Some studies have been done on using social relationships to increase the decision-making power of women. In the Bring A Friend study, women in Uttar Pradesh were encouraged to invite someone other than the husband or the mother- in-law to a doctor’s consultation about birth control. The idea being that a woman’s autonomy is primarily stifled inside her own family.

This study revealed that going for a consultation with a female friend increased the likelihood of women seeking modern contraception even in the face of resistance from the family and society at large. The analysis of Indian household structure reveals that the mother in law is a key influencer of household decisions and a study reveals that incentivising mothers-in-law may also help ensure that women are supported in their healthcare decisions. For women, having friends outside of the familial structure is also a key determinant of making good decisions on contraception.

The above studies indicate that any intervention which not only enables discourse on gender and equity but also educates and upskills women to make good decisions about themselves and their households will translate to women being confident about being active participants in decision-making both about important issues such as household management as well as healthcare. This will then ensure that health and nutrition related indices will show improvement as increased female autonomy is positively correlated with better health for both women as well as their family members. Hence it is important that more such interventions are introduced if we are to embrace the 2030 sustainable development goal and leave no women behind.

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.