[Readmelater]

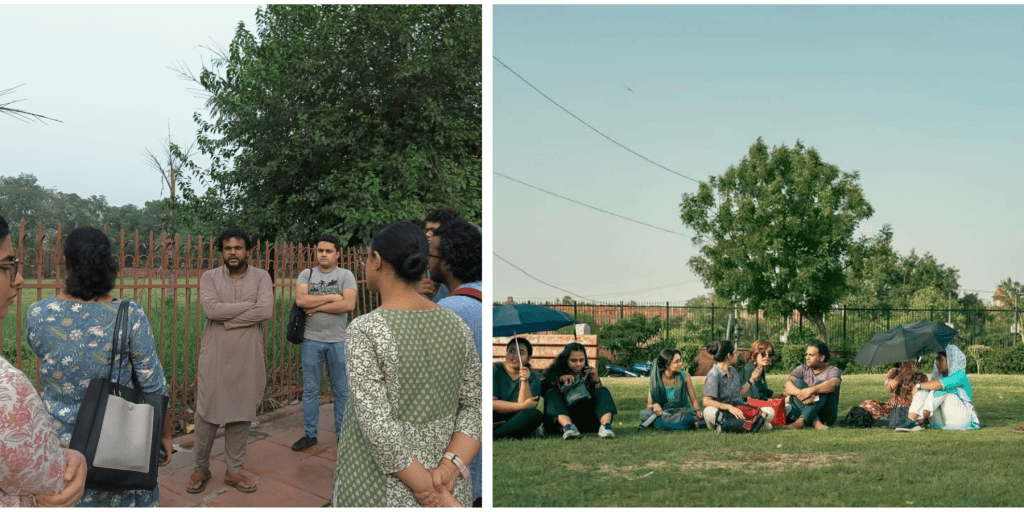

A Ramble Through Delhi’s Queer History, Told Through Monuments And Subcultures

A heritage walk looks at the capital city’s historic and contemporary spaces through the queer lens, revealing some less known insights

All photos by Ankita Dhar Karmakar

Support BehanBox

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.