[Readmelater]

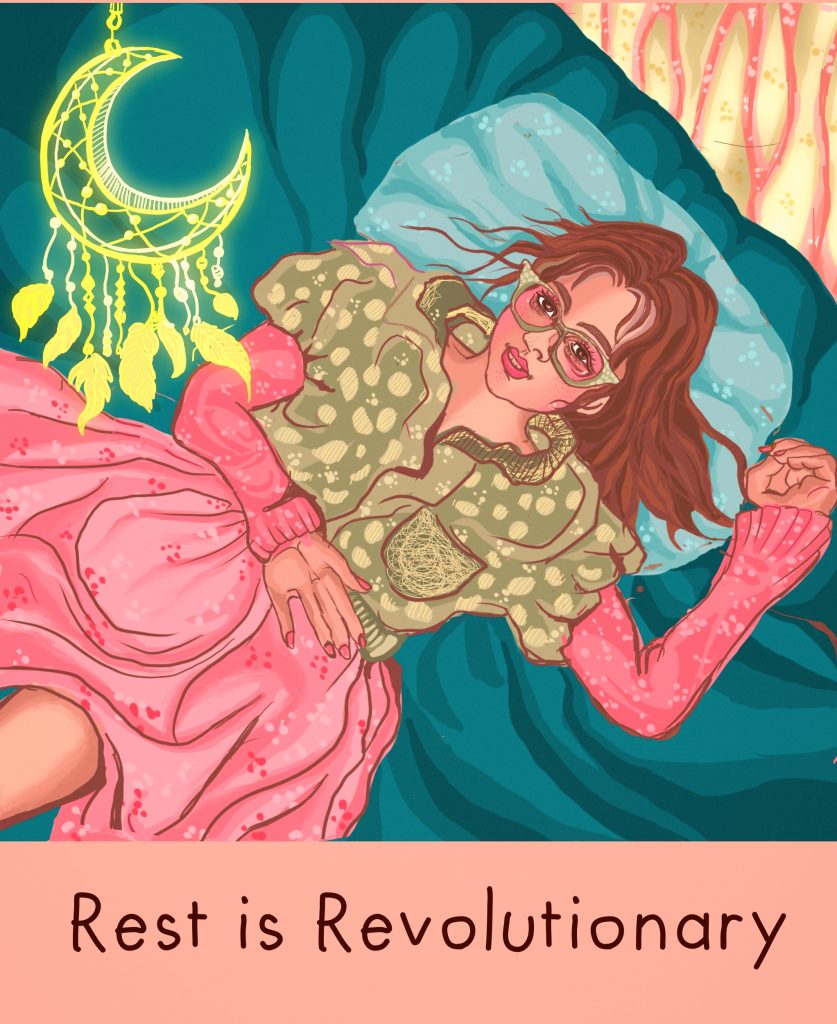

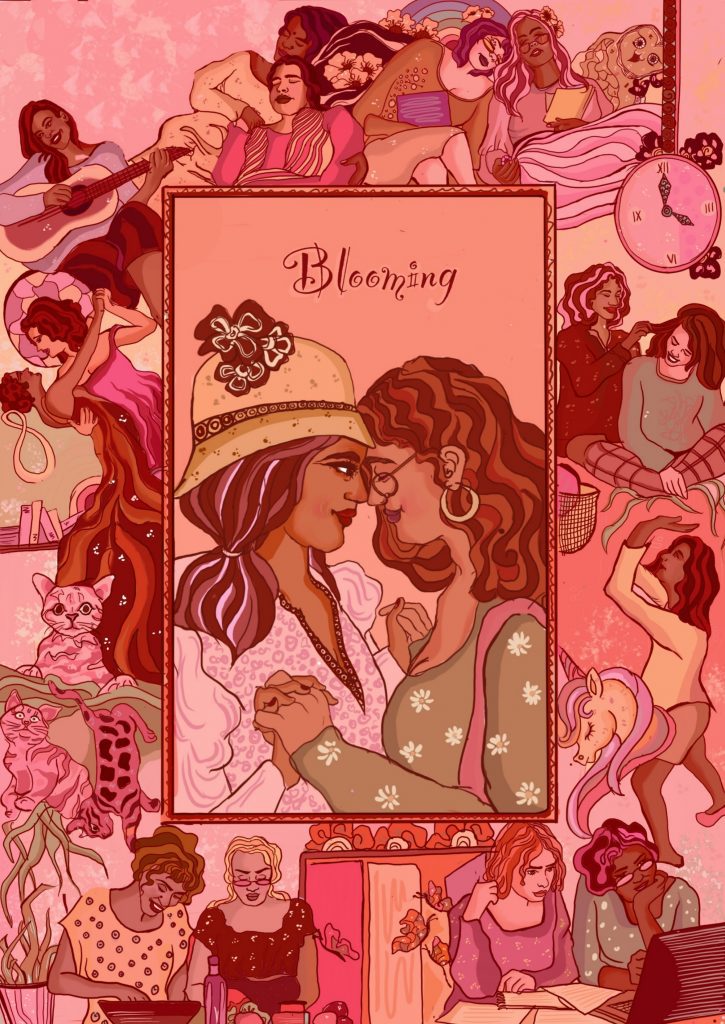

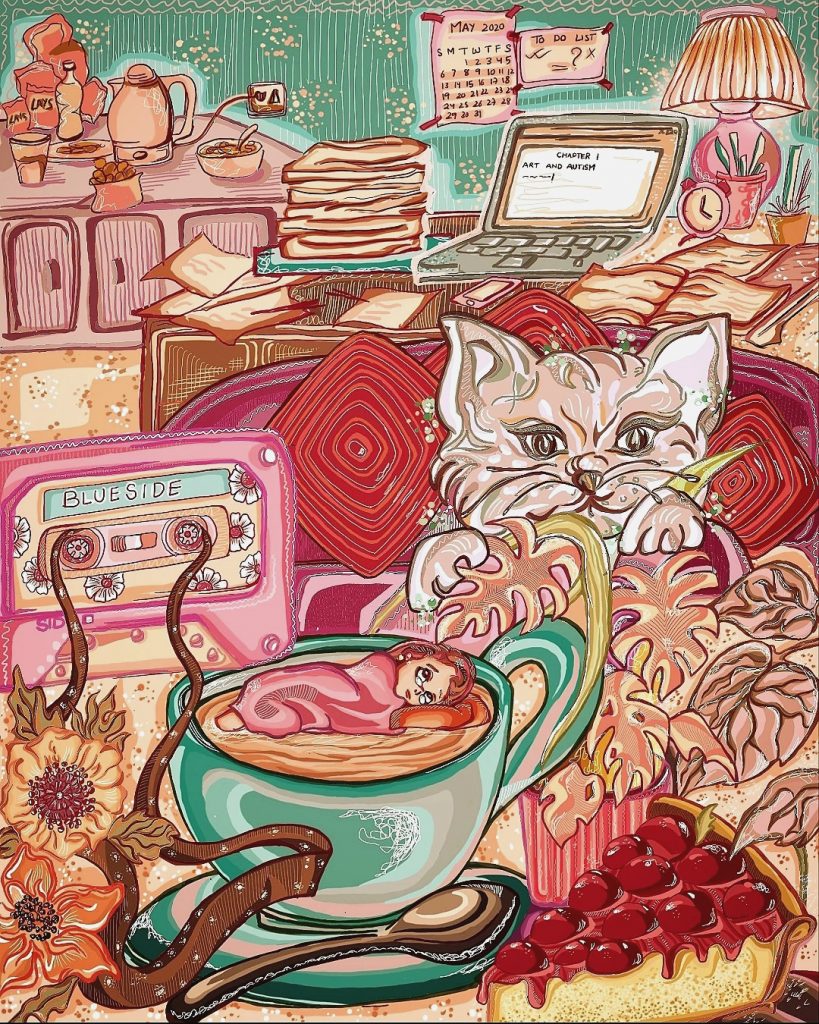

‘Digital Art Gave Me Control Over My Work As A Queer Disabled Artist’

Digital illustrator Ritika Gupta talks about the significance of the digital medium for neurodivergent artists and why community networks for disabled artists must thrive

All Illustrations by Ritika Gupta

Support BehanBox

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.