A Colonial Vestige, Why Marital Rape Exception Has Become Untenable

With the Delhi High Court currently considering petitions on criminialising marital rape in India, it is critical to look at the history, politics and ideology of the various arguments on the subject. The debate is currently playing out not just in the courtroom but also on social media.

India is among the 32 countries that have not criminialised marital rape. Section 375 of the Indian Penal Code, which defines rape as “sexual intercourse with a woman against her will, without her consent, by coercion, misrepresentation or fraud” has one significant exception based on the offender’s identity – when “[s]exual intercourse or sexual acts by a man with his own wife”. If, however, the husband and wife are living separately on account of judicial separation or otherwise, this exception does not apply.

The Centre has defended marital rape immunity by arguing that it protects men from its possible misuse by their wives and that it shields the institution of marriage. The Court was told that it would be difficult to determine the withdrawal of consent by a married woman, making it hard for the prosecution to establish any kind of corroborating evidence. The Centre also contended that laws on marital rape that apply in other countries do not fit India because of its unique socio-economic factors.

The petitioners arguing for the criminalisation of marital rape have argued that the exception is violative of fundamental rights to equality, life with dignity, personhood, sexual, and personal autonomy as protected under Articles 14, 19 and 21 of the Indian Constitution. They point out that marital rape exception creates an unreasonable classification between married and unmarried women. The assumption of “consent in perpetuity” cannot be legally valid as courts have recognised that consent can be withdrawn even during/in-between sex, they added.

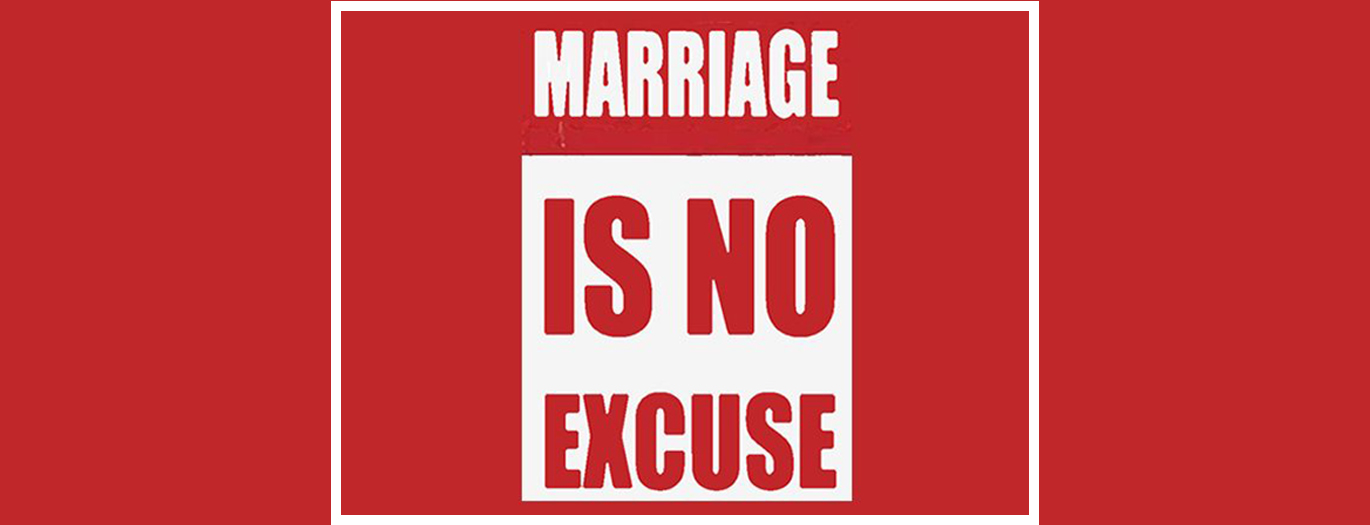

Activists and scholars have pointed to the regressive, sexist, illogical and colonial nature of the law that gives men a position of unquestioned control in marital sex.

Some of the High Courts in India have taken a progressive approach on this matter. In August 2021, the Kerala High Court held that marital rape is a valid ground for seeking divorce because it is tantamount to “mental and physical cruelty”. “Merely for the reason that the law does not recognize marital rape under penal law, it does not inhibit the court from recognizing the same as a form of cruelty to grant divorce,” noted the Bench of Justices A. Muhamed Mustaque and Kauser Edappagath.

The offence of marital rape is “a non-consensual act of violence perversion by a husband against the wife where she is abused physically and sexually”, said a single-judge bench of the Gujarat High Court in Nimeshbhai Bharatbhai Desai v. State of Gujarat while calling for total abolition of the marital rape exception.

But the Union Government has argued that the Courts can only issue an advisory, and not dictate the final outcome, which is otherwise the role of the Legislature. In its written submissions, it says, the “removal of exception 2 of Section 375 IPC which consciously would be akin to legislating a separate offence which can be done only by the legislature as per the doctrine separation of power prescribed in the Constitution of India”.

Congress MP Shashi Tharoor introduced a private member’s bill, The Women’s Sexual, Reproductive and Menstrual Rights Bill, 2018 in the Lok Sabha to amend certain provisions to “emphasise on the agency of a woman in her sexual and reproductive rights and to guarantee menstrual equity for all women by the State”. One of the suggestions was to criminalise marital rape to ensure a woman’s right to sexual autonomy even after marriage. However, the bill lapsed after it failed to garner support from the government.

Holding on to Victorian laws

The Indian Penal Code was drafted in the 1860s when, as a colony, India’s laws were largely influenced by Victorian patriarchal norms that did not recognise men and women as equals. As per the Unities Theory, a married woman was thought to be the chattel of her husband. As per 18th century English jurist William Blackstone: “By marriage, the husband and wife are one person in law: that is, the very being or legal existence of the woman is suspended during the marriage, or at least is incorporated and consolidated [into her husband].”

It was thus impossible at the time to fathom the idea of a husband “raping” his wife because it was presumed that he had unlimited privileges over her body. The exception to Section 375 was inserted in Clause 359 of Macaulay’s Draft Penal Code and retained in the final 1960s version of the IPC.

With the passage of time, and growing demands for gender justice and equality, this exception has become an anachronism. Problematic as it is, it is being justified on various grounds. Some men’s rights groups have argued that forcible sex between a husband and his wife cannot be labelled as rape, only “sexual abuse”. An NGO, Hridey, submitted that a woman cannot compel the Parliament to criminalise marital rape, and have her husband punished “to satify her ego”.

Another justification stems from the “implied consent” theory, the irrefutable presumption of consent between a husband and wife implying that a married woman willingly submits her autonomy to her husband in exchange for “protection”. Similarly, in accordance with the common law doctrine of coverture, a wife was deemed to have irrevocably consented at the time of the marriage to have sexual relations with her husband as per his whims.

A more recent argument is that the criminal law must not interfere in the private domain of a marital relationship. The hesitation can also perhaps be traced to the legislative disinclination to question an institution considered “sacred”. Maneka Gandhi, the minister of woman and child development in year 2016, used an argument that is still in currency: “the concept of marital rape, as understood internationally, cannot be suitably applied in the Indian context due to various factors like level of education/illiteracy, poverty, myriad social customs and values, religious beliefs, mindset of the society to treat the marriage as a sacrament”.

‘Instrument of oppression’

As stated earlier, critics of the exemption have argued for new thinking on conventional notions about marriage and women’s rights and choices, including those related to marital sex. The petitioners have submitted that until marital rape is criminalised “it will remain condoned”.

The amicus curiae for the case, Rebecca John, has described the immunity as an “instrument of oppression”. She argued: “What is written in exception 2, which has been given to us from a doctrine, propounded 200 years ago by our colonial masters, does not reflect either the Indian man or the Indian woman, certainly not the Indian marriage. The colonial masters have done away with it. We continue to hang on to that legacy.”

Senior Supreme Court advocate and former additional Solicitor General, Pinky Anand noted that the discrimination between married and unmarried women is “fatal to the understanding of gender roles”. Social scientist Sreeparna Chattopadhyay, associate professor at FLAME University, has pointed to the impact marital rape on the physical and emotional health of women and children. She argued that “the list is long and includes injuries, unwanted pregnancies, repeated abortions, poor reproductive and sexual health, a higher propensity to contract sexually transmitted infections, and poor mental health.”

Supreme Court advocate Vrinda Grover too has spoken about how the marital rape exception is “violence against women”.

The “sacred” argument

The issue of marital rape was discussed for the first time in the 42nd Law Commission Report (1971). It highlighted the presumption of consent when the husband and wife are living together, and the differentiation between marital rape and “other” rape. However, it did not comment on whether the clause on marital rape should be be retained or deleted.

In the 172nd Law Commission Report (2000) it was argued that there was no reason to shield rape from the ambit of law when other instances of spousal violence were criminalised. However, this argument was rejected outright by the Commission fearing that the criminalisation of marital rape would lead to “excessive interference with the institution of marriage”.

It was the 2012 Justice J.S. Verma Committee report that broke new ground on the issue. The ‘Report of the Committee on Amendments to Criminal Law’ advocated the criminalisation of marital rape by recommending deletion of the exception clause and specifically stating that the marital relationship cannot be a shield for the accused while determining consent. The report highlighted pointed to the sexist assumption of the immunity that “women being the property of men and irrevocably consenting to the sexual needs of their husband”.

However, the 2013 Criminal Law (Amendment) Act, drafted soon after the release of the report had no provision to criminalise marital rape. The Parliament Standing Committee on Home Affairs in its 167th Report refused to accept this recommendation because it would leave the “entire family system will be under greater stress and the committee may perhaps be doing more injustice”. Pointing to the private nature of marital relationships, the committee noted that families can resolve these issues as they evolve.

“Marital rape is difficult to define. In India, marriage is a sacred institution, and to include marital discord and resultant abuses as offences would be tantamount to delivering a blow to the social fabric,” said R.K. Singh, the then home secretary.

Former Chief Justice of India Dipak Misra, at a conference on ‘Transformative Constitutionalism in India’ in 2019, said that criminalising marital rape would “create absolute anarchy in families and our country is sustaining itself because of the family platform which upholds family values”.

Challenging the exception

The very first petition to challenge the legality of marriage exception was filed in the Delhi High Court in 2015 by an NGO, the RIT Foundation. The Supreme Court in Independent Thought v. Union of India (2017) decided that such an exception does not apply in cases where the wife is under 18 as it creates an arbitrary and discriminatory distinction between a married and unmarried girl child. The Bench also reiterated the importance of a woman’s autonomy over her own body, her right to bodily integrity, and her right to privacy.

Following this, petitions were filed by All India Democratic Women’s Association (AIDWA) and three individual petitioners along with the RIT Foundation, all being currently heard in the Delhi High Court. The three chief legal issues being argued at the court are:

Consent: The ‘implied consent theory’ sees marriage as a civil contract and the consent to sexual activities its defining element. The question here is how to define consent. It is argued that modern democracy cannot rely on old legal principles which regarded women as the “property” of her husband or had no decision-making power. Also a woman’s right to say “no” is an inherent part of her fundamental right to privacy and dignity and an “implied consent” need not be irrevocable.

Intelligible Rationale: Can the law be applied differently to married and unmarried women? Is the marital relationship grounds for “intelligible differentia” under Article 14 of the Indian Constitution? This would invest marriage with a special position that denies a wife the right to file a complaint against her husband if he rapes her. It is based on the assumption that the criminalisation of sexual activities between a husband and wife would have a “cascading effect on society and the marriage itself”.

Other Remedies: Supporters of marital rape exception say that married women already have adequate legal remedies through the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005, Section 498A of the IPC, and the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955. But the availability of these other provisions in various legislations are not sufficient to deal with the marital rape as under Section 375 of the IPC, it is argued.

The Centre, opposing the criminalisation of marital rape, has said that it cannot ape global laws blindly. “India has its own unique problems due to various factors like literacy, lack of financial empowerment of the majority of females, mindset of the society, vast diversity, poverty, etc”, it said in its written submissions. It also argued that making marital rape a “cognizable, non-bailable and non-compoundable offence” would block opportunities for settlement between the husband and the wife possible under Section 498A of IPC (domestic violence).

[Joshika Saraf is currently a Lecturer at Jindal Global Law School, O.P. Jindal Global University, India.]

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.