Dams Displaced And Changed Women’s Lives In Gujarat

If it were not for the pandemic, Raju Ben Vasava’s grandchildren would be at school. But, schools are shut, and Raju Ben, 55, is baby-sitting for the day. The children are a talkative bunch, taking time off only to munch on their freshly-picked pink guavas.

This is Kandbudi, a village in Southern Gujarat’s Tapi district, and here, children did have easy access to schools before the pandemic hit. But in Bej, 40 km away, where Vasava lived till 40 years ago with her husband, his parents and two children, school was a perilous journey away.

“In Bej, rivers would flow so violently during monsoons that our children could not cross them to go to school the entire season,” recalls Vasava.

Bej sat in the fertile land where the river Karjan, a tributary of Narmada, forked into two. Today, Vasava’s old home lies submerged under water all year round. In 1978, when the Karajan Dam began its construction, five villages, including Bej, went under the storage reservoir. By 1980, the Vasava family had to find a new home with the compensation money — Rs ₹6,200 for 2 acres of land.

The Vasavas chose to rebuild their life and a new home in Kandbudi, which over the years got populated with about 24 families with the same history.

Bej is now unfamiliar turf — when Vasava visits her mother’s home across the village, she has to take a boat that is rowed right over her former home.

“We had a big tree in our yard in Bej. When we row over our old home, we can still see the ends of its branches sticking out of the water, dukh lagta hai dekh kar [it is upsetting],” says Vasava.

The Vasava family made a living from farming in Bej but now everyone is engaged in non-agricultural professions. “We buy our vegetables, and Dediyapara [the block centre] is close-by for market, transport, and schools. I like living here now,” says Vasava. “Shanti hai [it’s peaceful].”

But, the move was not easy in the early days. “I used to cry every day. The language was a different version of Adivasi than that we were familiar with. I didn’t know anyone here. With our lands submerged and livelihoods gone, I was constantly worried that my children would go hungry.”

The Vasava family is not the only one to have suffered the pain of displacement in Gujarat. Across Gujarat, nearly 2.5 million households—one-fifth of the state’s population—have lost their land and/or habitat between 1947 and 2004. In south Gujarat alone, home to the Vasavas, an estimated 5.2 lakh hectares of land have been acquired for water resource projects alone.

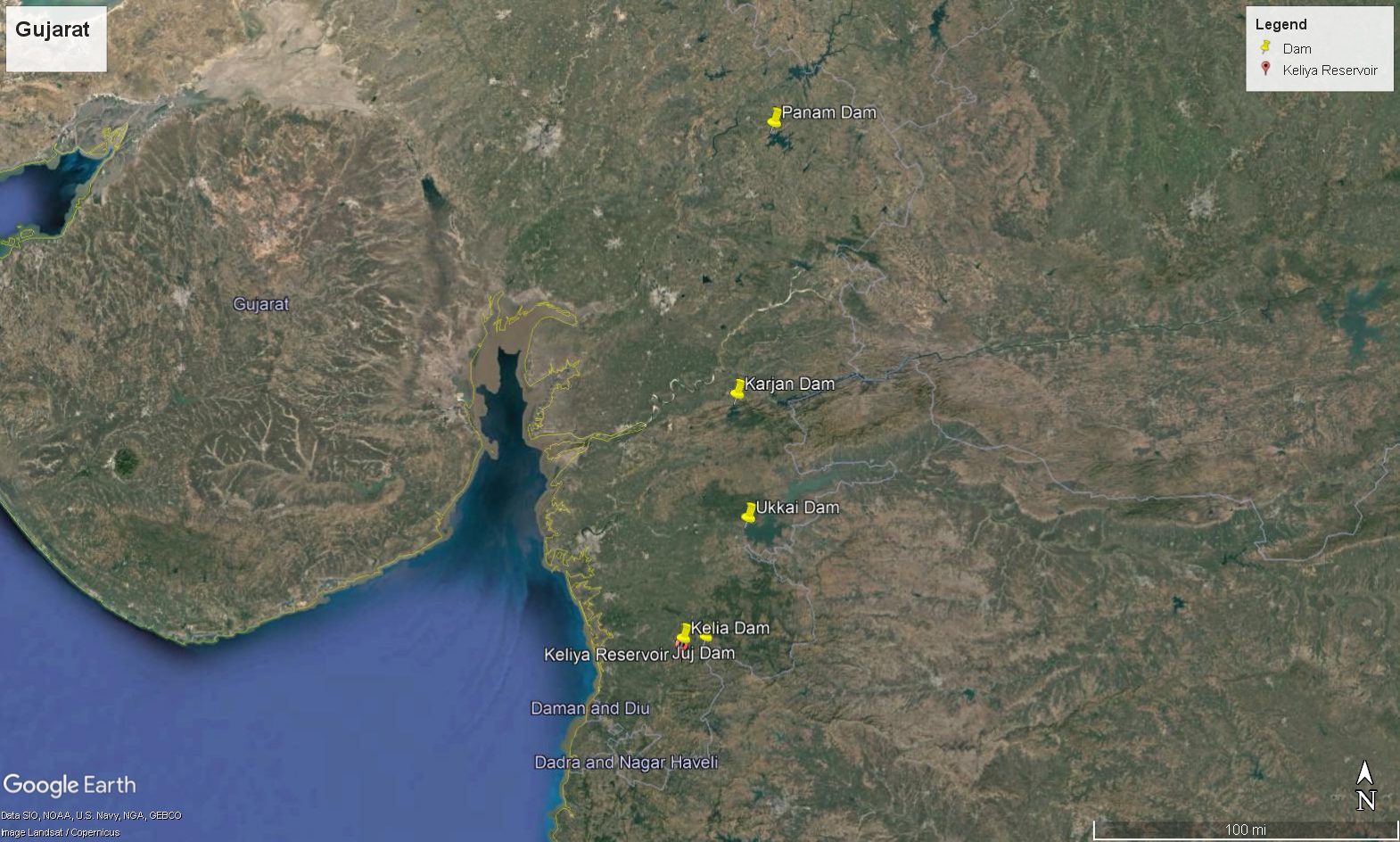

To understand how this displacement affected the economic, social and cultural lives of these families, we spoke to five Adivasi families in south Gujarat, who had to be rehabilitated due to the raising of four dams — Karjan and Ukai Dam in Tapi, Panam Dam in Santrampur and Kelia Dam in Navsari.

The rehabilitation impacted them all, one way or another. Some find their new life better, others are having a hard time dealing with it. But, one factor binds all these displaced families — the women experienced the resettlement differently from men. When families started their lives afresh, it was the mental and physical burden of the women that multiplied most intensely.

Increased forest dependence, but no legal recognition

More than 200 km north of the Vasava home, in Santrampur district’s Ajanwa village, a small patch of agricultural land lay fallow this April, when we visited. “We wait for the monsoon to grow corn,” says Geeta Ben Talar (55), who belongs to the Bhil tribe. “Jagah hoti toh kheti aur karte, ben (if we had more land, we could have farmed more, sister).” She has less than 1 guntha of land [less than 0.02 acres]. A pipe is attached to a borewell at the edge of her farm but it has run dry.

With sparse irrigation and such a small piece of land, Talar has to look for additional sources of income. One of these is in her backyard—a forest and its produce.

For two weeks every May, Ajanwa’s women walk to this forest to collect timbru (Bauhinia racemosa) leaves. Used to make bidis, 50 leaves fetch ₹1. During monsoons, the forests also yield vegetables, medicinal plants, mushrooms, and fodder. “When we go to the forest with our cattle, the Forest Department [staff] stop us often,” says Talar.

The women go to the forest to find fodder, cut it and carry it home. The work is time-consuming, laborious and disproportionately borne by women.

“In our old home in Vaghoi, we could grow rice and other crops throughout the year with our tubewell. We used to live like patels [a caste considered higher and thus with more accumulated capital],” says Suma Bhai, 62, Talar’s brother-in-law. The old family homestead where they lived till 1973, about 8 km away, had a tubewell which ensured at least two seasons of farming and lush grass to graze their goats and cows. This home, the village and at least 51 other villages, lie submerged in the waters of Panam Dam.

Vaishnavi Rathore

The problem is that despite the growing dependence of these families on the forest, the Forest Rights Act (FRA), 2006—a Central Act that legally recognised forest dependencies of Adivasis and other forest dwellers—does not secure their livelihood.

Of the over 600 FRA claims in four districts — Dahod, the Dangs, Navsari, and Narmada — only 30% had been approved, while over 60% were either pending or had been rejected, found a 2018 study by Working Group on Women and Land Ownership (WGWLO), a Gujarat-based network of over 40 NGOs and community-based organisations that, focus on women’s land and forest rights and sustainable agriculture by women farmers.

Even the land that Suma Bhai’s family bought with their compensation of ₹ 2000/acre does not show legal ownership. The family said they were cheated into buying a piece of common grazing land (shyamlat) from a family of grazers that did not even own it. Now, the Talars are trying to prove their dependence on the land under FRA so they can cultivate it but do not have enough evidence to push their case.

“The Forest Department has been asking us to pay fines for encroachment. To evict us from this land, officials became violent and hit my son,” Geeta Ben alleges. “For a while now, they [the forest department] have not troubled us but the thought th at they still can, because this land is not ours legally, is very stressful.”

The same problem dogs the residents of Songadh in Tapi. After the Ukai Dam, Gujarat’s second largest reservoir was constructed in 1972, displaced families moved to different villages. “Songadh was one choice but only areas of very dense forests were available for purchase with the compensation money,” says Ashwinbhai Mannchhabhai Gamit, who works as a paralegal on land issues with Dakshin Gujarat Vikas Sanstha, a part of WGWLO.

Gamit had earlier worked with displaced communities in Songadh in 2014-15. Resettled Adivasis had cleared forest land for farming here and they also came to bank on it for vegetables, firewood, medicinal plants and mahua flowers — collected for subsistence and sale. All these tasks are predominantly done by women. When communities here filed their claims under FRA, they received titles but with blatant errors, they allege. “Most families got their titles some 8-10 km away from where they found livelihoods,” says Gamit.

Can see water, but not use it

As the crow flies, Songadh is less than 10km from the reservoir. But the land on which families have been rehabilitated is on the dam’s right bank where irrigation channels have not yet been formed. Upto 59 more villages suffer the same fate. After a public interest litigation, the Gujarat High Court in 2012 ruled that a 36 km long canal project be completed in the next seven years on this bank. Only in some areas have the channels been dug.

“From their homes in Mandovi village [also on the right bank], people can see the water [in the reservoir] but can’t use it,” Gamit points out. “The water scarcity is so intense that in summers, many villages have to depend on tankers for drinking water.”

Some displaced families did end up on the side where irrigation projects reach. While this improves their agricultural productivity, the shift has added to women’s workload.

Increased workload for women

One such woman whose life has become tougher post-rehabilitation was Naju Ben Gamit (60). When Navsari district’s Kelia Dam was completed in 1983, her family, which lost its lands, moved to Mandav Khadak, just 4 km away. Here, a canal connected to Kelia channels water into the family’s fields. This constant supply ensures better agricultural productivity though the compensation from the sale of the 11 acres of land they owned earlier could only buy them 7 acres in Mandav Khadak.

However, the first few years of rehabilitation were hard, especially for the women. As the reservoir slowly neared completion, there was an interval when Naju Ben Gamit’s older plot had still not been fully submerged and the new one too had been purchased. The women would travel back and forth to cultivate both fields. They would sow, clear the weeds and harvest the crop, while the men ploughed with bullocks.

“For the first four years, we farmed both lands. And did house work too,” says Gamit as we sit on her porch in Mandav Kharak. Signs of economic prosperity like pucca houses and a few cars are visible in this village, likely thanks to the irrigation canal system. The road to their village is punctuated by the nahar (canal), brimming with inviting cold water on an April noon. Adjacent to these are fields with standing rice crops, an unusual sight because the crop is grown in monsoon.

Her neighbour, Lalita Ben Gamit, 40, married into this family after they were rehabilitated in Mandav Kharak, but she has heard stories about Kelia. “Nobody [in the family and other neighbours who had similar history] have forgotten about losing their villages. They still talk about it. We are still known as ‘Kelia-wale!’,” she says with a smile.

In Dholiwera, a small village in Narmada district, a few families still maintain connections with their old plots that were engulfed by the waters of the Ukai Dam. “A few families were able to buy some land with the compensation money, but in the dry months when their former lands emerge from the water, they work on that too. They grow moong dal, watermelon, and even rice there,” says Kirti Ben Vasava. Her father-in-law is one of many to resettle their families in Dholiwera. “But, the women make sure that all the crops are harvested by June.” As monsoon approaches, the dam waters reclaim these fields.

In their resettled village, after this harvest is done, women engage in “sukha kheti [dry farming]”, growing mostly red rice—a variety that can grow with just monsoon irrigation. Women’s farming burden has doubled here too.

Families fragmented

In Kanbudi—that now houses families that lost their lands to Karjan Dam—women face a different additional burden. Says Harilal Bhai Vasava (40) who was six when the relocation happened: “In our older village, my father and his three brothers lived together, which meant that the work in the farms would be distributed amongst all the wives.” But, after being displaced, joint families ended up splitting, with small units settling wherever they could find land.

“I feel this impacted my mother then because she had to work on the fields on her own as opposed to the collective efforts the women could put together earlier,” says Harilal Bhai. Their home has a ceiling with criss-crossed bamboo sheets. “My mother used to make and sell these [bamboo sheets] for additional income,” he says. His parents are no more so there is no one to share more vivid memories.

The relocation also stripped the family of another resource that nothing can compensate for—fertile grazing lands next to the river. “We used to own so many cows in our older village. Our milk production used to be so much that my mother used to make ghee out of the milk cream every seven days,” says Harilal Bhai. “But after coming here, sab khallas ho gaye [it all went]; this village did not have any grazing land that could support all those cows,” his brother, Gopal Bhai (43), adds.

Instead, women now collect fodder from forests for the cattle. Gopal Bhai’s wife was not available for an interview because she was out cutting grass. They offered me a pitcher of cool water, at least drinking water was not scarce here.

But 200 kilometres north from their home, even drinking water is not easily available. “We make at least four trips a day to fetch drinking water from a tubewell 1km away,” says Geeta Ben Talar of Ajanwa, Santrampur. This task of ensuring water for the kitchen is always a woman’s responsibility. “Where we lived before the dam took everything under, there was no tension about drinking water — we had a check dam barely 50 steps from our home,” adds Suma Bhai.

Women have no role in cash transactions

South from Suma Bhai’s home, a training programme on agroforestry by the government-run Krishi Vigyaan Kendra (KVK) is waiting to be inaugurated by district officials in Vyara, Tapi. At least 250 people are assembled at the venue. Almost all of them are women.

“We already grow sugarcane and rice,” says Sunita Ben, an attendee, over a post-event lunch of kadhi, rice, and chilled chaas. Her water-intensive crops flourish because of the healthy criss-cross of canals in Vyara channeled from the Ukai reservoir in the neighboring Tapi district. “I will now try and experiment with agroforestry.”

Sunita Ben is an example of most women with whom discussions were held during the course of this ground reporting. When it comes to all things farming, they participate in decision-making. All agreed that their contribution is equal in agriculture, if not more than that of the male members of the family. While their opinion may not always be considered, they are confident about planning what crops to grow and seeds to store for the next year. But, this confidence does not translate to handling cash. So, when lands were acquired for irrigation projects and compensation given, women were nowhere in the picture.

“I don’t know why my father-in-law chose this village to buy land in, and how much compensation we got when our land was acquired,” says Vasava. “He decided all of those things, and we just landed up.” In all the families we interviewed, the patriarchs of the family—husbands, fathers, fathers-in-law, and brothers—made the decision of how the compensation money was to be spent. This resonates with previous research findings that a direct cash transaction “disempowers women” who tend to be “less able, within the family, to influence decisions related to how the money is to be spent”.

For women, compensation money substituted land, a resource that they knew well, tended to and had some stake in. Women found themselves responsible, especially for the well-being of their children, and yet did not have the agency to influence decisions on family spending. This multiplied their mental stress. As Mandav Kharak’s “Kelia–wale” Lalita Ben shared, “There was only a certain amount of money given for compensation, barobar (right)? Now, decisions on setting up home with this money, buying new land, ensuring that the children get to eat — all had to be made. Women would worry about this.”

Emotional cost

Rehabilitation also left women more emotionally drained than men. They had worked as labour to construct the dam that ultimately submerged their fields. “We were so happy that we got good money so close to our home till the dam was completed,” says Vasava. “We were earning ₹3 per day constructing the Karjan dam which was very good for the time. Lekin, ghar doobta dekh kar dukh hua [watching our house submerge felt bad]. Even after we got the compensation money, till the time we settled properly, we regretted it [hum pachtaye].”

Today, families have moved on but are still holding on to small parts of their old lives by farming on their old lands when they can, fighting court cases, and identifying with the names of their old villages even though Google Earth now shows them submerged under water.

[This story is produced as part of the WGWLO-BehanBox reporting fellowship on women’s land, forest and farming rights in Gujarat]

This story is edited by Malini Nair.

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.