Sulli Deals: Online Platforms Fuel Cyber Sexual Violence Against Muslim Women

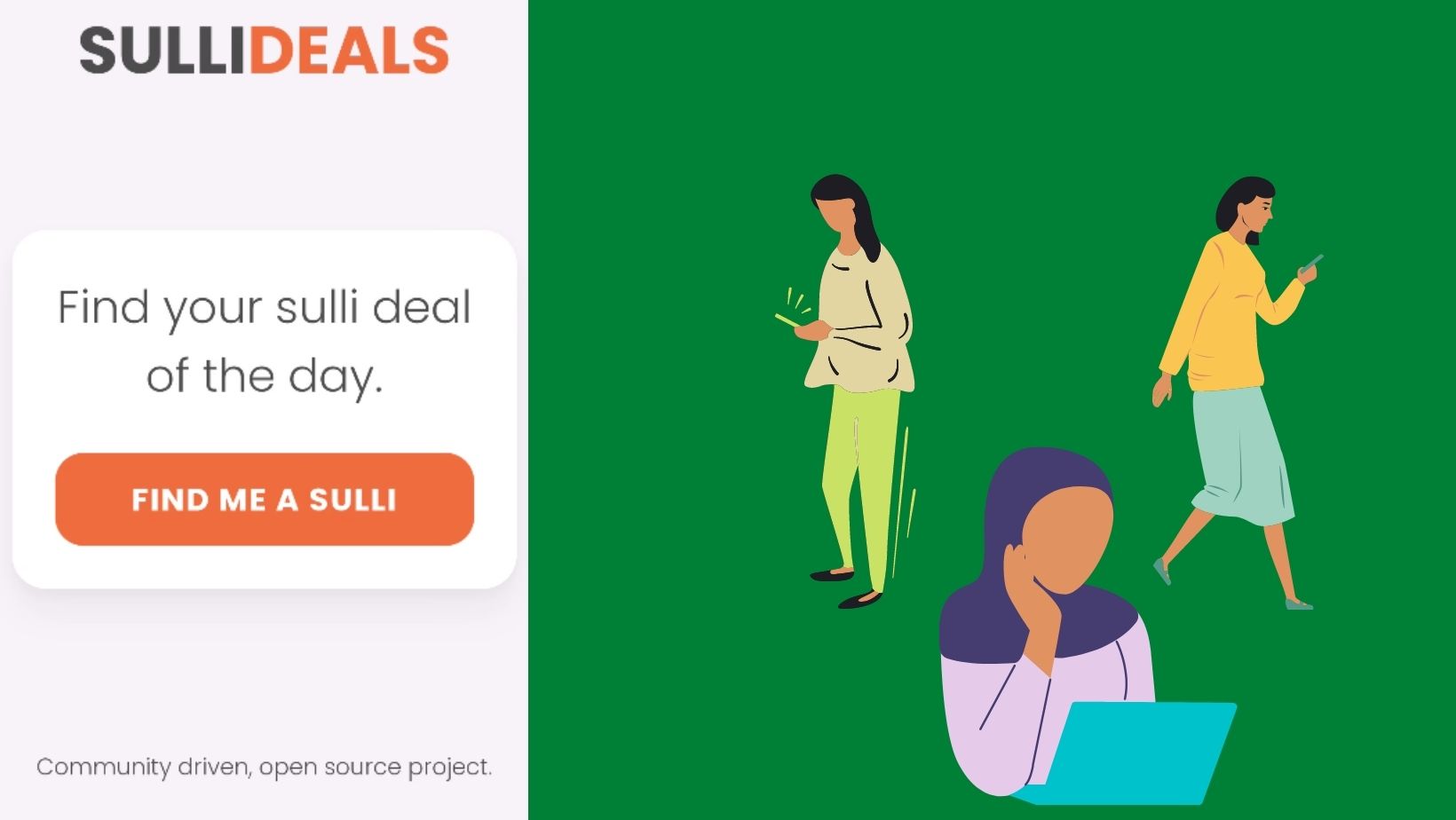

Shaikh Tabinda received a message from her friend, on the night of 4 July, which read that she had been ‘sold’ in an online ‘auction’ on an app called ‘Sulli Deals’. The message had screenshots of her pictures where she had been offered as the “deal of the day” to users on the internet. Users, then, had the option of sharing their ‘deal’ on Twitter.

Tabinda was shocked.

“I was numb when I saw the screenshots. I could not bear opening the link to see pictures of me being sold”, the 22 year old MBA student and activist told BehanBox.

Fifteen minutes later, the app was taken down, after a complaint was made to Nat Friedman, the CEO of GitHub, an open source platform that hosted the app. But those fifteen minutes left Tabinda traumatised for days.

“I felt violated, my dignity was attacked. It made me furious,” she said. “I did not leave my bedroom for the first few days, fearing how I would face my parents.”

Tabinda was one among approximately 90 Muslim women, whose online profiles were auctioned on the Sulli Deals app – described by the makers as a ‘community driven open source project’. Sulli is a derogatory term used for Muslim women, especially by the Hindu right wing entities.

Tabinda believes that the app only targeted educated, outspoken, and articulate Muslim women–journalists, researchers, activists and artists– with a considerable online presence.

“The app is an attempt of the Hindu right-wing to humiliate and silence opinionated and influential Muslim women since our presence contradicts their narrative that paints us as submissive and oppressed burqa-clad women”, said Fathima Zohra, a 26, a lawyer and social worker, whose profile was among those auctioned on the app .

“They must not be confused with trolls because this is an organised ecosystem”, she said.

Zohra chose to fight back.

She filed two complaints, one at the cyber police station and another at her local police station in Saki Naka in Mumbai, the day after the incident. Following her complaint, the Mumbai Police issued letters to Twitter and GitHub on 7 July, asking the platforms to share details of the accounts that created and promoted the app.

National Commission for Women (NCW) and the Delhi Commission of Women (DCW) took suo motu cognizance of the issue and wrote to the cyber cell of the Delhi Police seeking a detailed action taken report.

The cyber cell registered an FIR under Section 354-A (assault or criminal force to woman with intent to outrage her modesty) of the Indian Penal Code. They also sent notices to GitHub to share relevant details, said the Delhi police.

This is not an isolated incident, but one in an increasingly vicious pattern of cyber sexual violence, targeting Muslim women in India.

Rising cyber sexual violence

A day before Eid, in May this year, a YouTube channel called Liberal Doge, live-streamed an online auction of Muslim women from India and Pakistan. Titled “Eid Special”, the channel run by Ritesh Jha, with more than 85,000 users, egged users to “rate” and “auction” women whose profiles were picked from their social media accounts without their consent, reported Prateek Goyal of Newslaundry. The user comments during the ‘auction’, reports Goyal, were both misogynist and Islamophobic.

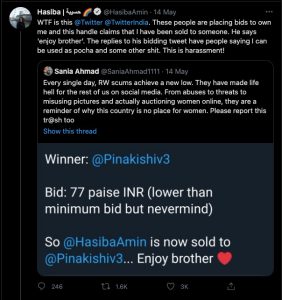

The bidding later moved to Twitter where handles such as @desisullideals and @sullideals101 participated in the auctioning.

Hasiba Amin, the national convenor of social media for the Indian National Congress, and journalist Sania Ahmed were two of the many women whose profiles were auctioned.

Chronicling the pattern of cyber sexual violence, journalists Alishan Jafri and Zafar Afaaq have revealed an organised social media activity by the Hindutva rightwing handles that objectified ‘Muslim women as sex objects for Hindu men’. Amin’s profile was “sold off” by a user with the words ‘enjoy brother’. Right wing handles have been circulating phone numbers of Muslim women asking other Hindu men to ‘marry and treat Muslim women as public property’.

Such cyber sexual violence is cheered on by many with almost mob like behaviour. After the Eid incident, a hashtag #ISupportLiberalDoge was trending on Twitter. More recently, Ajeet Bharti, the former editor of OpIndia, an Indian right-wing news portal, celebrated the Sulli deal portal as a welcome step in the use of open source technology.

Twitter and YouTube accounts of the users such as Jha, were only temporarily suspended after complaints to the cybercrime portals, only to resurface later with changed names. There has been no legal action in this matter.

Amin lodged a complaint to the Delhi police on the National Cyber Crime Reporting portal, which was recently displayed as “closed”.

“The communal nature of this case cannot be ignored. Such cyber violence against Muslim women has been normalized and these complaints are hardly followed up on”, said Anas Tanwir, the lawyer representing Amin and Ahmed. This goes beyond simple trolling and needs to be framed as an attempt to abet trafficking of women, says Saif Alam, a lawyer representing Zohra.

“To curate a list of women along with their data and then auction them as “deal of the day” amounts to trafficking”, he said.

Scarred for life

When Noor Mahvish, a third-year law student, discovered that she had been ‘auctioned’, she feared being closely watched on social media.

“The picture they used of me was an old one.They must have had my data for a while now and that is scary. Who knows, they might be watching me in real life too”, she told BehanBox.

She mustered courage to file a complaint after three days.

“I don’t feel safe leaving my home since the incident. ‘What if they hurt my family’ is the one thought that keeps haunting me. Since my sister’s name was also on the list, I feel they were coming for my family members too”, said Zohra.

“Fatima is a lawyer and has the support of her family. Most women cannot even tell their parents because of the stigma in our society to incidents like this. Most families would first question the girls about why they had been using social media or had uploaded their pictures online”, said Saif Alam, Zohra’s lawyer.

Many women, like Zohra’s sister, whose names and pictures were used, have now deactivated their social media accounts. Many like Amina (name changed) have done it fearing similar cyber sexual harassment for being Muslim.

“Soon enough, the media and people will forget about this incident. But I have been scarred for life”, said Mahvish.

Mirroring Real Life violence

The vitriol hurled at Muslim women online borrows from and mirrors real life hate campaigns by Hindutva groups.

“This case must be seen in the context of the current socio-political atmosphere marked by calls for violence against Muslim women” said Zohra. “They openly talk about killing unborn babies of Muslim women. We have seen what they did with women during the Gujarat pogrom in 2002. It scares me to even think of what these people are capable of doing,” she said.

In a video that went viral recently, Thakur Shekhar Chauhan, who claims to be the chief of the Karni Sena in Uttar Pradesh was seen exhorting the mobs to drag pregnant (Muslim) women out of their homes and kill their unborn babies if a single Hindu is harmed, to rousing chants of ‘Jai Shree Ram’ by his supporters.

Rambhakt Gopal, the person who shot at a student at the anti-NRC/CAA protests in Jamia last year, called upon Hindu men to avenge “Love-Jihad” by abducting Muslim women in a recent Mahapanchayat organized by the right wing, Vishwa Hindu Parishad in Gurugram.

Both Gopal and Chauhan have been arrested.

“It should not surprise us that they are using sexual harassment as a tool to silence us. They are the followers of V.D. Savarkar who advocated for use of rape as a political tool”, said Mahvish

Rape and calls for sexual violence and bodily possession, enveloped in Hindutva pride, emerged as a pattern after the abrogation of Article 370 in Kashmir in August 2019, when the BJP MLA Vikram Saini asked the bachelors to rejoice because they could now marry the “fair-skinned” girls of Kashmir. Social media platforms, at the time, were replete with posts and videos of Hindu men fantasizing getting married to Kashmiri women.

“The normalisation of violence against Muslim women over the years, as seen during the Gujarat pogrom, Muzaffarnagar riots, Delhi pogrom, and Mumbai riots, has created an atmosphere conducive for such crimes. There are people who actively come out in support of the perpetrators just because the victim is a Muslim woman”, said Noor Mahvish.

Hate Crime

Tears ran down Noor Mahvish’s face as she entered the police station to file her complaint.

“I kept thinking, ‘Is it so easy to comment on Muslim women’s bodies publicly?’”

“Some people have reduced this to a case of misogyny and patriarchy alone. But I disagree.This is clearly communally motivated”, she says. “I have faced Islamophobic incidents in the past but this is something completely different. They have attacked mine and the dignity of the women of my community,” Mahvish asserts.

The Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) defines hate crimes as crimes motivated by prejudice or bias towards a group or a community that shares a common characteristic (such as race, gender, ethnicity, religion, or sexual orientation) primarily because they hold views and beliefs contrary to one’s own.

A group of more than 800 women’s organisations, activists and individuals have released a statement reiterating that this was a targeted hate campaign against Muslim women in India and abroad, which puts their life and liberty at risk.

“They keep telling us ‘you’re oppressed’ but when we showed them that we’re not, they attacked us like this”, says Tabinda.

While these incidents of cyber sexual harassment violate several provisions of the Indian Penal Code (354A, 354D, 370 r/w 511, 505, 506, 507, 509) as well as the Information Technology Act (Sections 66, 67, 72), lawyer Vrinda Bhandari, who works on digital rights and privacy issues, believes that this should be categorised as a hate crime.

“I would add Section 153A, 295A of the IPC, because the offence is specifically targeted at Muslim women. It is also important to frame these offences as hate speech and recognise the communal angle of the offence, the derogatory use of “Sulli” to target Muslim women”, said Bhandari.

Accountability of platforms

These incidents of Islamophobic cyber sexual harassment, coming in quick succession, point towards the inadequacy of the regulatory and redressal systems of social media platforms.

Twitter’s ‘Hateful Conduct Policy’ puts the onus of reporting incidents of hateful conduct and abuse on the aggrieved persons. Journalist Sania Ahmad believes it to be unreasonable that the “onus should be put on women to run after these cases and be threatened and abused more in the process.”

Tanwir, her lawyer, sent a legal notice to Twitter demanding that the platform take action against these accounts by permanently suspending and banning them from future use of the platform. He also suggests that platforms should ensure inclusion of local languages and their transliteration to recognize violent threats in languages other than English.

Saif Alam, Zohra’s lawyer, has faced difficulty in getting social media platforms to comply with the investigation requirements. He told BehanBox about a website, “sullidealing.co.in”, hosted on GoDaddy. While the website has now been taken down after complaints, the domain name still exists on the web hosting company.

“We are certain that this is the work of an organised ecosystem. If we are able to track down the owner of this domain, it will help the investigation. GoDaddy.com has refused to give information to the Mumbai police on the details of the owner of the domain. They have asked for a subpoena instead ”, said Alam.

“I believe it should be mandatory for these websites and social media platforms to comply with such requests made for the investigation of a case, especially if it is coming from a law enforcement agency,” he said.

“The problem is that an offence such as this is not specifically provided for in the IPC”, said Bhandari. “ Amending Section 66E of the IT Act would be an easy fix, which can handle non-consensual uploading of photos online, without necessarily adding more criminal provisions in the law”, she said. Section 66E is one of the few provisions in the IT Act that puts consent and hence, autonomy at the heart of the offence.

The current redressal mechanisms of social media platforms suffers due to a lack of direct synergy between the social media companies and local police on the reporting standards mandated by the National Crime Records Bureau( NCRB) write Mitali Mukherjee, Aditi Ratho and Shruti Jain in their paper ‘Unsocial Media: Inclusion, Representation, and Safety for Women on Social Networking Platforms’. They also observe that vague definitions for gendered abuse, violent behaviour and harassment make subjective targeting of individuals easier along with the fact that police are more likely to take action on physical threats and traditional criminal laws.

“The patriarchal nature of the criminal prosecution system advises women against filing complaints in such matters, playing down the severity of the crime for the lack of a “real physical threat”, said Tanwir. In most cases police officials discourage women from filing complaints because they just don’t want to work, he adds.

Hasiba Amin and Sania Ahmed, represented by Tanwir, plan to approach the Saket court in Delhi to reopen the case and launch an investigation into the incidents prior to Eid.

Facebook, Google, TikTok and Twitter made a commitment to tackle online abuse and improve women’s safety on their platforms at the recent UN Generation Equality Forum in Paris, by improving their reporting systems.

Meanwhile, women, especially from the marginalised communities, continue to face the brunt of inadequate redressal mechanisms. Shaikh Tabinda, Fatima Zohra and Noor Mahvish, however, are resolute in their decision to fight against these hate crimes.

“We may be disturbed right now but we stand strong by our decision to resist this,” said Tabinda.

“They’ve been taking advantage of the nature of the judicial processes in India but I will fight this case even if I have to fight till my last breath. I will do it for myself and for my community,” asserts Noor.

“I need to be able to answer for myself when the future generations ask me what I did to fight back,” Zohra.

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.