Women With Disabilities Invisibile In Covid Policy Responses

“My bhabhi is pregnant but has no place to deliver. We are scared of catching Covid. We’re still facing the (basic) challenges. The biggest challenge for women with disabilities during the Covid pandemic is employment. I am myself divorced and have 2 kids to look after. We can’t even approach others for help”, said Anuradha Pareekh Executive Director of Sajag Divyang Seva Samiti, a disability rights group during the webinar on women with disabilities and Covid-19 crisis in India.

“My disabled sister and her husband, who are tailors, are earning much less. In such precarious times, disability that makes it worse.”, she adds.

Anuradha is not alone.

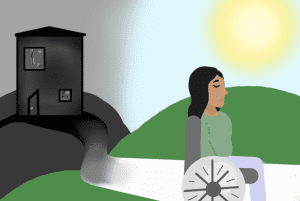

Women with disabilities found their struggles exacerbated during the Covid pandemic. Inequities that were endemic before, were heightened manifold due to lack of clear and accessible information and several barriers to exercise their agency, livelihoods, nutrition, education with severe impact on their mental health and emotional well-being.

As India announced a complete lockdown, one of the strictest in the world, to contain the Covid-19 outbreak on 24 March, 2020, once again, persons with disabilities were excluded from the response systems and policy. This exclusion has been highlighted in a recently released report “Neglected and Forgotten: Women with Disabilities during the Covid Crisis in India” by Rising Flame, a non profit working on the human rights of people with disabilities and Sightsavers International. The report researched and authored by women with disabilities themselves, captures the voices and experiences of 82 women with disabilities and 12 experts across 19 states across the country and highlights the poor policy response of the government of India with regard to persons, especially women with disabilities.

‘In India, there are 11.8 million women with disabilities who experience considerable challenges, discrimination, isolation and marginalization in their routine lives. They are not considered to be “woman enough” and routinely discriminated against or abused and harassed; they face barriers in various aspects of life and this gets heightened during the current crisis. Responses should differentiate the particular needs of women and girls with disabilities, but also the specific needs they may have within each specific disability’, noted Nidhi Goyal, founder and executive director of Rising Flame.

India has ratified several laws that support women with disabilities, such as United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), the Convention on the Rights of Child (CRC) and the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). It is also signatory to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

India also has several laws such as the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (RPD) Act 2016, the Mental Healthcare Act 2017, and Criminal Law (Amendment) 2013 which share the same commitment. The Government has also issued the Disability Inclusive Guidelines under Section 8 of the RPD Act which outlines the necessary steps that state governments need to take to protect the rights of persons with disabilities.

Despite the multitude of laws in place to ensure the rights of women with disabilities, the ground realities indicate that not much has been done to implement these guidelines.

Disabled Women Face Barriers to Access Information, Technology and Mobility

Since the beginning, the lockdown did not have a disability inclusive approach. For instance, despite the provisions of the Disability Inclusive Guidelines to make Covid-19 related information in accessible formats, the declaration that was made late evening by Narendra Modi, the Prime Minister of India, did not have captioning or sign language interpretation to that could enable persons with disabilities to prepare for the impending lockdown with a narrow 4 hour window.

92% of the participants in the research who identified as deaf, deafblind and hard of hearing faced access barriers with regard to information, physical spaces, digital spaces, health services, food and essentials and digital education.

Even the Aarogya Setu, an app that is considered crucial by the government in tracking and navigating the Covid crisis has not been accessible to the persons with disabilities. Digital platforms had failed to take into account the several intersectional inequalities that the women with disabilities face.

Several women said they were unable to garner very important services because of difficulty in accessing physical spaces. They could not get the support of their caregivers which made important tasks impossible, such as going to the ATM, public transit, buying groceries and other essential supplies.

A 42-year-old woman with scleroderma (a wheelchair user), Faridabad, Haryana speaks of her unpleasant experience

“Since I am on oxygen, I can do very limited tasks. I can sit and work for hours but if there is anything physical it is a big challenge. It takes around an hour and half to take a bath and get ready. I used to get little support earlier, but after the lockdown began, I have started doing it alone and this takes a lot of energy out of me.”

Lack of Access To Food and Essential Supplies

“I had gone to buy some ration, and there my crutches slipped. I fell down. In normal times, someone definitely used to come to pick me up if this sort of a thing happened. But that day, no one came. Then I took out my sanitizer from my purse, and gave it to the shop- keeper, and then he came to help me get up”, said a 39 year old with locomotor disability from Ahmednagar, Maharashtra

Women with disabilities had difficulty accessing food and rations during the pandemic. While urban women with disabilities could manage somewhat due to online ordering, this is still not an effective solution for the assistance required.

Women dependent on the Public Distribution System (PDS) for their rations had a harder time. While the Central and State governments had directives mandating assured access to food and essentials and dedicated supermarket times, women with disabilities in states had to physically go to PDS shops to buy ration as far as 5 km away and were often not prioritised.

“ As for ration, other than wheat and rice, we are not getting anything else. It has been one and a half months; supplies have got over”, said a 39 year old woman with a locomotor disability from Ratlam in Madhya Pradesh.

Even then, women with disabilities had to stand in the same line as everyone else, she said.

In a survey conducted by the National Centre for Promotion of Employment for Disabled People (NCPEDP), it was found that 67% of people with disabilities reported to have no access to doorstep delivery by the government.

Healthcare Access Restricted

Many women with disabilities, due to weaker immune systems or comorbidities, have a greater risk of contracting the coronavirus. Besides, during the pandemic lockdown, they have had difficulties in accessing healthcare services. Many have had to go to private hospitals and pay a higher cost for treatment.

“My 11-year-old daughter is in extreme pain. There is no female doctor in our village and Bikaner district is 30 km away. So, we need conveyance to go. Our financial condition is not that strong in this situation. The drivers who used to charge Rs. 1000 to drive to Bikaner, are now charging Rs. 2500. We do not have enough money to take the car and drive to the doctor. My back is in pain”, said, a 38-year-old a daily wage earner with locomotor disability from Bikaner, Rajasthan.

Technology Gap In Access To Education and Employment

50% of the participants reported a disruption in workspaces and feared losing their earning capacity. Women with disabilities faced technological gaps both in education and employment due to lack of multi-sensory communication.

“No special assistance, no captions or text are shared. Most of the assignments are PDFs scanned and sent which mean someone needs to read out to me”, said a 20-year old deaf and blind college student from Delhi

Another 35-year-old woman who is hard of hearing from Mumbai, Maharashtra shared her difficulties.

“During physical meetings and face-to-face interactions, lipreading was easier, but with so many people on the call, it was very time consuming and tiring to lip read and understand what people were saying. Also, many colleagues were not considerate enough to keep their videos on all the time or speak slowly. Due to this, I missed a lot of content discussed during meetings and could not participate.”

School girls faced particular discrimination as they were the last to obtain electronic devices for their studies. Even teachers with disabilities found themselves playing catch up.

Impact on Mental Health

This current isolation has also left many women undergoing mental stress which is often ignored in the conversations about women with disabilities.

More than 50% women reported going through loneliness and isolation.

Women with disabilities reported facing different forms of violence- physical abuse, financial abuse, neglect, threats, misbehaviour/misconduct, abandonment, and emotional abuse.

They are at higher risk of domestic violence due greater reliance and fewer lesser opportunities to exit, lack of caregivers and shelters.

“My family told me that they could not support me physically or my expenses anymore and asked me to return to my husband’s house with my small daughter”, said a 42-year-old woman with locomotor disability (Scoliosis) from Thane in Maharashtra

A young girl’s family in rural Chhattisgarh refused her basic essentials to her till she completed all household chores.

Many activists also felt their inability to help during the lockdown had taken a toll on their own mental health.

“There are people who want to talk to me but I am not able to meet them personally. One of the patients wanted to meet me and talk to me but I could not go. She died within two weeks and I felt very guilty. I felt I didn’t do justice to her.” said a 38-year-old woman from Trivandrum who is the trustee of an organization that offers palliative care to patients

Lack of Social Protection Adds to the Vulnerability

Article 24 of The Rights of Person with Disabilities Act, 2016 places an obligation upon the government to formulate schemes to ensure that persons with disabilities have an adequate standard of living to live within the community or independently.

“Persons with disabilities are to be given equal access to retirement benefits and to public housing programmes. The quantum of assistance for persons with disabilities is mandated to be higher by at least 25% in schemes for the general public. The schemes envisaged under this provision include support in times of manmade or natural disasters”, said Ketan Kothari of Sightsavers International in the webinar on women with disabilities.

Despite this, women with disabilities have not been provided with adequate social security.

The report noted that 34% women in the study- from Rajasthan, Chattisgarh, Bihar, Maharashtra and Assam- had not received Rs. 1000, an ex gratia Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Yojana Scheme, was to be made available to PwD who were eligible for the scheme. Many did not receive their pensions, ranging Rs. 300 – Rs. 2700, during the lockdown, while others had to go to banks to access the cash transfers without assistance.

“The cash is directly transferred to the account of the disabled women. Many times, husbands keep the ATM cards and take the money and spend it on alcohol etc. Money should be given in cash by home delivery to the person herself”, said a 39-year-old blind woman, Bhubaneswar, Orissa.

How Can Policy Be More Inclusive?

The report from the ground points out the shortsightedness of the government in providing basic support to persons with disabilities, especially women with disabilities. This neglect shines a light on the need for a larger paradigm shift to protect the rights of those who are more vulnerable, especially those who face an intersectional inequity. The growing marginalisation faced by the women during the period of this pandemic calls for a holistic systemic response.

The Disability Inclusive Guidelines issued by the Department of Empowerment of Persons with Disabilities need to have a gender inclusive response to ensure access to food, essentials (including menstrual care products), quality healthcare and rehabilitation for persons with disabilities with a clear budgetary allocations and accountability mechanisms.

The report asks for the inclusion of women with disabilities in leadership roles and disaster management training task force to respond sensitively. It calls for continuous monitoring of access to information, food, health and social security schemes for a more nuanced response for the different disabilities.

Government needs to ensure equal accessibility in education and employment and affirmative action to minimise the risk of girls dropping out and discrimination against the women in workspaces. The National Commission for Protection of Child Rights should frame mandatory directives to schools on the inclusion of children with disabilities.

The recommendation also calls for more support systems like helplines, websites, and other appropriate grievance redressal mechanisms for these women in case of discrimination and abuse. Helplines should be more inclusive of women and girls with disabilities and eliminate barriers to reporting.

[ Vasudha Varadarajan is a recent graduate from Azim Premji University with a Masters in Development. Her interests lie in gender and ecology. She is an intern at Behanbox.]

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.